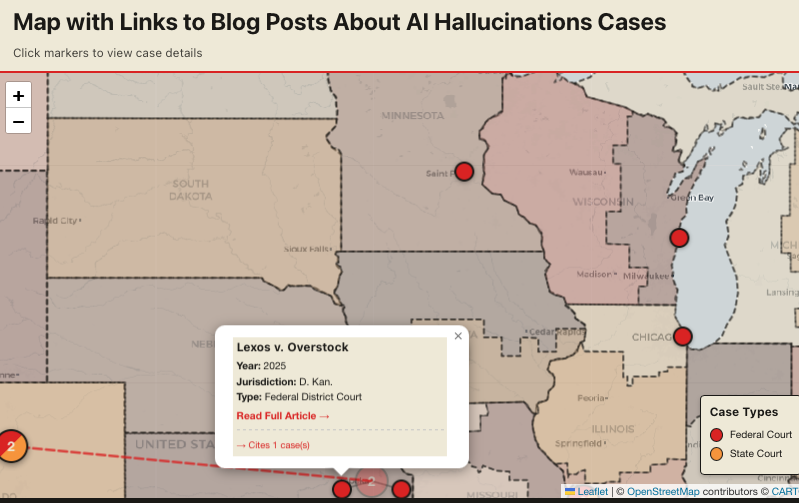

“Who Cares About Signature Blocks Anyway?” District of Kansas, Apparently.

I was listening to the latest episode of the legal podcast Advisory Opinions, “Must and May,” which covers a variety of topics, including a minor discussion about signature blocks. A comment caught my attention because of its relevance to generative AI misuse.